Creating an Accessible Platform for Kava Farming Knowledge

With the rising popularity of the kava beverage and the kava bar, kava has become not only a traditional crop for ceremonial and personal use but an important cash crop for both the Pacific Islands’ local market and for export. The cultural significance of kava continues to be a significant and vital part of Pacific Islander life today. Kava’s use has continued to expand with products diversifying beyond the kava beverage and the demand for kava coming from people and entities outside the Pacific Islands.

Although kava production in the Pacific Islands has a history spanning millennia, much of that history was retained and passed along through oral histories. Farmers in one area of the Pacific Islands might not be aware of kava farming practices in another area and previously did not have an accessible platform to access additional knowledge or share their knowledge.

The Secretariat of the Pacific Community printed Pacific Kava A Producer’s Guide (henceforth referred to as simply the “guide”) in order to fill this knowledge gap so that anyone who grew kava plants or was interested in growing kava plants would be able to access a reliable source of information. The guide was written to “supplement traditional knowledge and to encourage experimentation, adaptation, and the use of improved farming practices.”

About the Guide

The guide was based on much of the technical publications by Dr. Vincent and the result of the collaborate efforts of many including but not limited to Mr. Jerry Konanui of the Association for Hawaiian Awa, Mr. Jim Henderson of Puu ’O’ Hoku Ran, participants of the Regional Kava Meetings in 1997 and 1998, Dr. Richard Beyer, Profesor Bill Aalbersberg, Ratu Jo Nawalowalo, Reg Sanday, and Dr. Ron Gatty.

The guide contains “the principles for producing high quality kava as a commercial crop for both the domestic and the export market” as well as chapters on the “chemical properties of kava and on the standards that are recommended for the increasingly discerning domestic and export markets.”

The guide thus begins to demystify the complexities of growing kava plants and also touches on the concerns surrounding kava quality control and standardization which are increasingly becoming an issue as kava becomes more widespread outside of the Pacific Islands.

As such, sharing perspectives from this guide is useful during the journey of demystifying the root of happiness and insights from this guide will be dispersed throughout subsequent kava conversations. The guide is broken into the following overarching themes:

- Piper methysticum

- Kava—Diseases and pests

- Kava—Planting

- Kava—Harvesting

- Kava—Post harvest losses—Prevention

And covers the following specific topics:

- Production

- site selection

- planting material

- direct planting

- nurseries

- transplanting

- planting and spacing

- cropping methods

- soil and plant nutrition

- weeding

- water requirements

- pruning

- pest and disease management

- Harvesting

- harvesting and yields

- harvesting techniques

- Post-harvest handling and marketing

- washing

- cutting and sorting

- drying

- storage

- commercial parts of the kava plant

- kavalactones

- high-quality kava

- quality specifications

- advanced processing

- marketing

- Hawaiian kava production

- False Kava

Kava Production

The guide first emphasizes that “one of the most important decisions a farmer needs to make is selecting a suitable site for growing kava” with the ideal site for growing kava being “mixed cropping fields.” This means that the kava can ideally be planted in fields with other crops such as taro, maize, yams, and sweet potatoes. Shady conditions are preferable making kava well suited for Pacific farming systems “because [kava] is well suited for Pacific farming systems because it is flexible in its cultivations requirements and thrives in the shade during its first three years of grow.” Kava production can often involve crop rotation, intercropping, and planting of windbreaks, shade trees, and leguminous tree species.

Although there is substantial diversity in kava cultivars in the Pacific and differences in the content of kavalactones in different cultivars, kava has a very narrow genetic base. The narrow genetic base is due to the fact that “kava does not produce viable seed so there is no possibility of cross pollination to create new cultivars.” The diversity has rather been “caused by farmers selecting mutant kava plants with desirable characteristics for personal and ceremonial use.”

Because kava can only be grown through vegetative propagation from cuttings from existing kava plants, selecting planting materials is a crucial and important decision. Generally speaking, it must be from a desirable cultivar and a healthy and vigorous plant in order for the kava beverage to have desirable drinking characteristics and in order to prevent the spread of diseases and causing crop losses.

Traditionally and historically, direct planting (planting stem cuttings directly in a field) was the primary method to grow kava plants. However, this method has been abandoned in many areas for the following reasons: it requires more planting material and longer pieces; it requires extremely moist conditions and much watering; it is difficult to achieve the desired spacing necessary to optimize kava plant production; and it is difficult to provide sufficient shade when compared to a nursery.

Nurseries have presently become a popular and successful method for farming kava. Nurseries are more efficient and kava plants have a higher survival rate in them. Nurseries provide adequate shading, enable adequate watering and spacing, reduce weeds, and have reduced labor costs because weeding time is reduced and “the transplanted seedlings are bigger and stronger and need less care.”

Four kava nursery methods detailed in the guide are:

- planting one- or two-node cuttings in nursery beds

- planting one- or two-node cuttings in plastic bags

- germinating whole kava stems in nursery beds

- planting four-node cuttings in plastic bags

Kava plants should be gradually exposed to direct sunlight and then removed from the nursery when they are ready for transplanting into a field. Transplanting should be done when the kava plants are 30 cm tall, the moisture conditions in the field are good, and the land has been cleared of weeds.

Kava is often planted together with root crops in subsistence gardens on cleared ground. Monocropping of kava is not recommended in the Pacific Islands because it can promote and spread disease and is not good for long-term soil fertility. Intercropping is particularly advantageous because it can prevent diseases and can help provide shade and sunlight when necessary.

Currently, there are is no recommendation as to what is the best combination of crops when farming kava. Kava is often grown with many different crops in the same field and the crops are changed over the four-year growth cycle of the kava.

Common intercropping combinations include:

- kava and coconuts

- kava and sweet potato

- kava and peanuts

- kava and ginger

- kava and vegetables

- kava and taro

- kava and pigeon pea

Soil preparation is minimal, and kava can grow on a variety of soils. However, the soil should have good drainage and preferably be deep and loose. Kava roots cannot withstand oxygen starvation and poorly drained or heavy clay soils. Oxygen starvation would also promote bacterial and fungal diseases. Kava plants are heavy feeders and its vigorous growth depends on rich soils.

Compared to plants that live as long or grow as large as kava, kava has a very limited root system that does not extend very far laterally or deep into the soil. After the first three years of growth, kava plants have taken all the nutrients from the soil and can then suffer “nutrient stress” making the plant highly susceptible to disease. Composting, mulching, and the addition of animal manure are necessary to combat these issues and ensure the maintenance of healthy kava plants.

The guide states that a major constraint to the intensification of cropping systems today is “kava dieback disease.” Kava dieback disease refers to the rotting of kava stems from the apex or from the nodes to the stump. Evidence suggests it is linked to low soil fertility and nutritional stress. A lesser constraint on the intensification of cropping systems is fungi that live as a parasite in kava rootstock leading to the kava root rotting and the plant subsequently dying within three weeks of infection.

Harvesting Kava Plants

Most of the labor associated with kava farming comes from harvesting and post-harvest handling. Harvesting kava plants involves removing the upper part of the plant, cutting the stems above the first node, and taking care to harvest the valuable roots without breaking them. These kava roots can reach a thickness of 30-60 cm (1-2 feet) and measure over 2 meters in length (6 feet).

Harvesting, handling, and drying the kava have a major impact on the quality of the kava and the price and thus should be given particular attention. Most of the time kava is harvested after three to four years of growing but for local ceremonies, “kava plants may be grown for over ten years before harvesting.”

The kavalactone —the active ingredient in kava and the ingredient which provides its pharmacological effects—content of kava plants increases with age and can sometimes even depend on the type of soil, the availability of nutrients for plant growth, and the kava variety. The kavalactones content as well as the proportion of each of the six different kavalactones present in kava are indicative of the quality of the kava. The kavalactone content also varies depending on the part of the plant: 15-20% in the lateral roots, 8-12% in the stump, 5-8% in the basal stems, 2-5% in the stems, and 1-2% in the leaves.

After harvesting, postharvest handling and marketing involves washing, cutting and sorting, drying, and storing. Kava roots are washed, peeled, cut and sorted into basal stems, peeling of root stock, chips of root stock and roots, and residues. Each of these parts are kept separately because the kavalactone content and price of each part is different.

Fresh kava rootstock is, on average, 80% water and thus different technologies have been developed to expedite the drying process. These include clear and black plastic solar dryer as well as vented roof design solar dryer. Then dried kava can be stored in a fashion similar to that of other dried agricultural products. Because dried kava root is hygroscopic—it attracts and absorbs moisture from the air particularly in high humidity climates such as the Pacific Islands—the rootstock may have to be dried out again after a few months of storage. The following additional points about dried kava root storage are noted in the guide: kava will slowly reabsorb moisture unless protected in a moisture –proof container, it can be stored at any temperature below 50 degrees Celsius if it is stored in a moisture proof container, the moisture content of the kava must be monitored and tested, the kava can be dried again if necessary, but multiple drying will cause the quality of the kava to deteriorate.

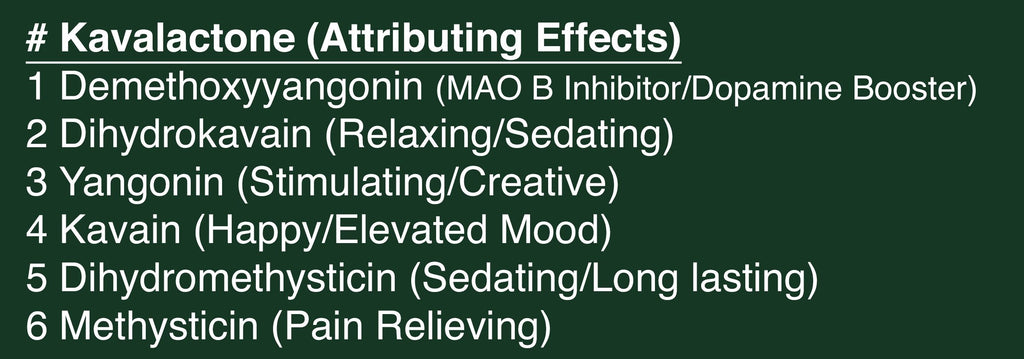

Kavalactone Content

There are fifteen kavalactones with different physiological properties that have been identified in kava. They are divided into “major” and “minor” kavalactones with six major kavalactones (dimethoxy-yangonin, dihydrokavain, yangonin, kavain, dihydromethysticin, methysticin) accounting for 96% of the fat soluble extracts from kava and are thus the most important active ingredients. Some kavalactones—such as kavain and methysticin—can now be synthesized but synthetic kavalactones do not produce the same physiological effects as the kavalactones from kava. This is because the “efficacy of kava evidently does not stem from a single active substance but rather from a mixture, a blending of several kavalactones that results in a synergistic physiological effect.”

When it comes to organizing and distinguishing kava cultivars, kavalactones are numbered in the following way:

- 1= dimethoxy-yangonin

- 2=dihydrokavain

- 3=yangonin

- 4=kavain

- 5=dihydromethysticin

- 6=methysticin

Then the kavalactones are listed in decreasing order of the proportion of a particular kavalactones present. This six number sequence is referred to as a “chemotype.” For instance, the chemotypes of two popular Vanuatuan kava cultivars are 246531 and 426134. The first three kavalactones listed in the chemotype are “normally represent over 70% of the total kavalactone content” meaning that kava consumers and supplies pay particular attention to the first three kavalactones of the chemotype. The two aforementioned Vanuatuan chemotypes both have dihydrokavain, kavain, and methysticin as their first three kavalactones.

The chemotype of a kava cultivar has varying importance to local drink market in the Pacific Islands but has increasing interest by the European pharmaceutical industry and in the areas of alternative and complementary medicine where they will only purchase kava that has certain chemotypes. The kava industry has responded to this specific demand by increasingly cultivating preferred chemotypes.

High Quality Kava through Good Harvest and Postharvest Practices: Age, Cleaning, Drying, Heat Damage, Sorting, Foreign matter or kava residues, Appearance and aroma, Storage

The following list is taken from the guide and states that higher quality kava will be produced if the kava:

- is at least three years old

- is clean and free of soil

- is dry

- is not heat-damaged

- is free of mold and mildew

- is separated into peelings, chips, roots

- contains no foreign matter or spent kava

- has good appearance and aroma

- is stored in clean bags under good conditions

Quality Assurance

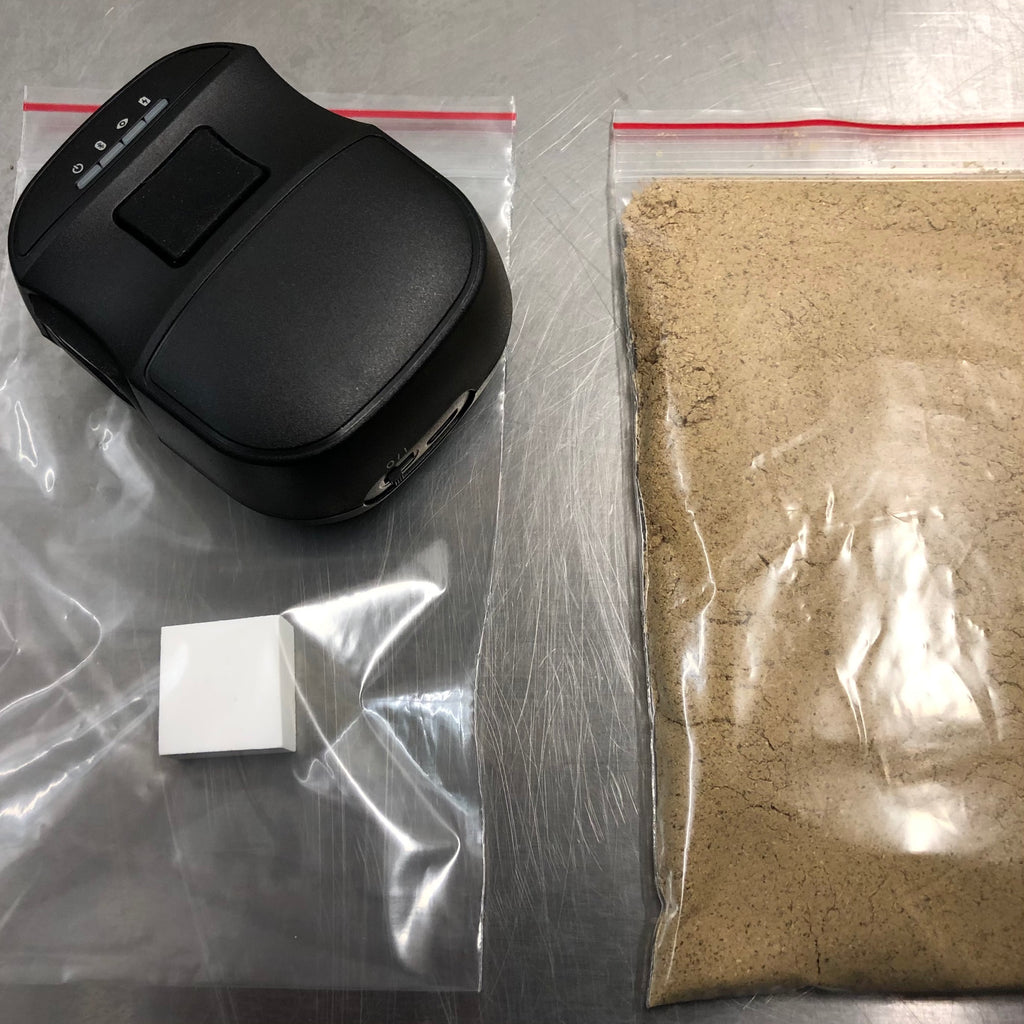

As kava becomes more popular, expands outside of the Pacific Islands, and expands into different industries, quality assurance becomes a more and more relevant issue. Quality specifications—“a pre-sale agreement on the quality of the product which is to be traded”—exist for many products, are relied upon to facilitate the trading of products, and are enforced by the industry/exporters/legislation. Quality assurance and monitoring consist of taking and testing a representative sample of the product.

Kava has been traded and consumed for millennia without any formal quality specification. Rather, the buyers and middlemen relied on their experience to examine and determine the quality of the kava. Naturally this informal arrangement was not without problems. However, the historically informal nature of quality control in the kava has not been without issues. And these issues have been exacerbated by the international interest in kava.

There is currently no physical or chemical quality specification for kava exporters to the pharmaceutical industry which has led to buyers and exporters experiencing problems and rejection of exported kava.

As countries outside the Pacific Islands become involved in the international kava trade, “more advanced analytical techniques have been introduced which have led to the introduction of detailed, indisputable quality specifications for kavalactones.” The guide points out that “the establishment and use of a quality specification for kava can protect Pacific Island kava producers and traders in the event of a dispute over quality.”

The Institute of Applied Sciences of the University of South Pacific was funded by the Secretariat of the Pacific Community in 1995 in order to draft a quality specification for kava.

Their quality specification includes the following factors that are normally included in the quality standards of a commodity (taken directly from the guide):

-

Description

-

“The official description for a quality specification normally contains the botanical name and a brief description of the product. Thus adulteration means that the product does not conform to the specification and the purchaser may reject the consignment. it can be difficult to visually detect adulteration but there are tests that can detect when other vegetable matter has been added. Adulteration has been common in the food industry and a number of instances have been reported in which kava has been adulterated with ‘spent’ (used) kava and other matter.”

-

“Kava will be the roots, rootstock, basal stems or scrapings derived from the plant Piper methysticum. It will be sound, clean, and substantially free from filth, soil, and other contaminants. it will be prepared in accordance with good manufacturing practice and will not contain vegetable matter derived from other species, insect fragments, or any other extraneous matter.”

-

-

Physical Properties

-

“A series of simple physical tests can give a quick, easy assessment of quality.”

-

Flavor

-

“This can be tested informally by simply preparing a solution and assessing it…taste panels in which as many as 20 panelists assess flavor, appearance, and aroma can be used for dispute resolution.”

-

-

Filth

-

“It is important to remove as much soil as possible from the kava to ensure that the bacterial level is as low as possible and to ensure that the purchaser does not in effect pay for soil.”

-

-

Moisture

-

“The keeping quality of vegetable matter depends to a large degree on the moisture content. Reducing the moisture content below 12% is essential.” Too much moisture would make the kava moldy. Roots breaking easily and laboratory oven-drying techniques can also be used to determine moisture content.

-

-

Chemical Characteristics

-

Ash

-

Ash testing is an inexpensive and simple indicator test that “gives a guide to other characteristics such as age, cleanliness, moisture content, and contamination with other plant material.”

-

-

Kavalactones

-

Kavalactone content is arguably the most important characteristic of kava. There are “accepted values” of kavalactones content and the kava should fall within these values in order to be deemed acceptable for export.

-

-

-

The following are proposed kava quality specifications based on research at the Institute of Applied Sciences at the University of the South Pacific (taken directly from the guide):

-

Physical characteristics

-

Color

-

Kava should be light brown/grey in color.

-

-

Aroma

-

“The aroma will be free of extraneous aromas indicating contamination with other plant material, solvents, or other volatile matter.”

-

-

Flavor

-

“In the event of a dispute, kava samples will be subject to a taste panel assessment using the triangular taste test. There will be at least 20 panelists and results will be subjected to a statistical analysis.”

-

-

Filth

-

“Heavy filth exceeding 0.63% but less than 0.7% will be considered second grade. Heavy filth exceeding 0.7% will be rewashed and re-dried.”

-

-

Moisture

-

“Moisture content exceeding 12.54% but less than 12.88% will be considered second grade kava. Kava samples with moisture content in excess of 12.88% will be redried.”

-

-

Chemical Characteristics

-

Ash

-

“Samples exceeding 5.36% [ash content] but less than 5.93% will be considered to be second grade kava. Samples with an ash content in excess of 5.93% will be washed and redried.”

-

-

Kavalactones

-

“A quality specification for kavalactones content is still under development and it is very difficult to specify because of the great variations between the kava varieties. The important point, especially if large consignments are involved, is the need for both buyer and seller to test the kavalactone content. Once the results are available prices can be accurately negotiated.”

-

-

-

Processing Kava for Use in the Pharmaceutical Industry

There are different processing techniques utilized for kava use in the pharmaceutical industry and field of alternative and complementary medicine since these fields prefer kava in the form of a capsule. In order for kavalactones to be extracted and contained in capsules, two methods can be used: solvent extraction and spray drying.

Solvent extraction refers to extracting kava with volatile solvents. This is the most commonly used method for extracting kavalactones for pharmaceutical use because it the cheaper of the two methods, volatile solvents don’t leave a residue in the kavalactone extract, and volatile solvents are recyclable by evaporation and distillation. The kavalactones extracted this way form a “dark thick viscose substance that is not easy to use directly” and must be “combined with an inert substance such as starch to create a powder with 30% kavalactone content that is then placed in capsules.”

The steps in the solvent extraction process include the following:

- Dry matter

- Crushing

- Reduction to fine powder

- Maceration, hot or cold in a solvent

- Filtration

- Elimination of solid residues

- Evaporation and recovery of solvent

- Extraction of a brown colored resin

- Resin mixed with a base to create a 30% kavalactone powder

This method of processing enables kavalactones to be extracted from kava residues from domestic consumption—in other words, this type of processing enables kavalactones to be extracted from kava residues that are not used when making the traditional kava beverage and that traditional methods do not have the ability to extract.

Solvent extraction has been touched on in previous kava conversations as there are mixed reports about its safety and the effect it has on the pharmacological effects of kava—more scientific research needs to be done on its safety but generally speaking, research appears to show that kava extracted with organic solvents appears to be safer than traditional pharmaceutical alternatives like benzodiazepine BUT traditional kava beverages and kava extracted with water has a much longer and well-known, safer history than kava extracted with organic solvents.

The second method for processing kava for the pharmaceutical industry that the guide highlights is “spray-drying.” Spray drying refers to a “well-established agro-industrial technique that produces water soluble powders such as milk powder that are easy to handle and store.” This technique suits kava well because the “powder dissolves in water and it is more rapidly absorbed by the body in this form than in capsules.” However, this technique is very expensive requiring an initial $500,000 investment into a small spray dying unit capable of processing the fresh kava root.

The steps in the spray drying process are the following:

- Fresh root

- Crushing

- Filtration

- Fresh juice

- High pressure pump

- Spray drying

- Water-soluble powder obtained

The kava extract produced during the spray drying process still bears some resemblance to the ceremony and traditional preparation of the kava beverage. Thus the guide argues that “for the local market and export, there is a need for a high quality, pre-dried, ground kava for those who want to consume kava in this manner.”

Although there has been interest from the private sector in establishing kavalactone extraction facilities in the Pacific, the guide states that “large pharmaceutical companies and natural products companies have substantial investments in their own processing facilities to use with a wide variety of raw material,” and “they prefer to use their own processing facilities to control quality and in order to add value to the raw material themselves.”

Domestic and International Markets for Kava

There are several specific markets for kava that are distinct from each other and should be treated as such. These markets include:

-

The Domestic Drinking Market

-

This refers to the local market in the Pacific Islands which remains important in terms of cultural value, total size, and cash value. Middlemen often buy kava from rural areas and resell it at urban centers. Apparently, there is “increasing demand for pounded kava sold in packets for local consumption in kava shops and in private homes.”

-

The domestic drinking market tends to be low-risk when compared to the export market because relatively small quantities of kava are involved and there is much transparency surrounding the producers, buyers, and prices.

-

-

The Export Market

-

This refers to the drinking market outside of the Pacific Islands, the pharmaceutical market, kava bar, and the nutritional supplement market. Kava exporters often have buyers whom they work through, but some kava farmers do sell directly to exporters and have partnerships with overseas kava buyers and processors.

-

Kava has been a part of the pharmaceutical industry for a while now in Europe—specifically in France and Germany where it has been considered a valid alternative to harsher pharmaceuticals like Valium and other benzodiazepines. This market is very precise in that the demand is for kava with a specific chemotype and “the pharmaceutical laboratories process to the kava to make a capsule with an exact kavalactone content.” In the U.S., kava has been present in the market as a dietary/nutritional supplement as well as a social beverage.

-

-

Buyers

-

This refers to those who serve the market (not individual consumers) and who are “interested in finding the lowest price possible for a high quality kava.” In this market, sorted kava is preferable to pounded kava so that the quality can be verified immediately. Price is then determined by quality, consistency, part of the plant, and supply and demand.

-

Kava’s Potential for Growth

There is excellent potential for growth in the local and export kava market. However, there remains room for improvement when it comes to filling knowledge gaps regarding kava including the areas of production, research, marketing, and organic certification. Specific points taken directly from the guide are detailed below:

-

Production Research

-

It appears that further market opportunities are constrained by production since the large domestic market can restrict the amount available for export. Kava needs increasing attention as a commercial crop where effective cropping systems are adapted to local conditions for smallholders as well as a large-scale plantation. Organic kava production systems also need further seedy because of the high-value niche market for organic products. There are also major bottlenecks and needs for agronomic research:

-

Establishment of national germplasm collections

-

Selection of kava varieties of the best chemotype and kavalactone content

-

Hawaii has already undertaken thus and subsequently, only “good” chemotypes are promoted for production.

-

-

Development of reliable tissue culture techniques and micropropagation systems for virus-free planting material.

-

Hawaii has made progress in this area but the survival rate of plants from tissue culture was only 50% at the time of publication

-

-

Identification, prevention, and control of existing kava pests and diseases—including dieback—and a comprehensive study of the epidemiology.

-

Determining the suitability of kava monocropping by smallholders in the Pacific

-

Kava fertility management for maximum production and sustainability

-

-

Processing Research

-

There needs to be further research into appropriate processing techniques as well as appropriate equipment and packaging techniques for smallholder and for large-scale production. Priority should be given to the improvement of spray drying techniques, ultra-high temperature treatment, and identifying the ideal combination of organic solvents for the treatment of residues from domestic consumption (if such a combination exists). National Kava Councils should be established to encourage initiative and coordinate the development of the industry.

-

-

Facilitation of Marketing Activities

-

Kava quality specifications need to be established so that inconsistent supply and poor quality does not destabilize prices and inhibit market development. National or regional names should be developed and protected to symbolize quality kava from original sources and to protect it from competition from other sources.

-

-

Organic Certification

-

The organic market is a valuable niche market with the potential for Pacific Islands kava producers. Much of the kava grown in the Pacific Islands is grown without the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers to begin with. An organic certification system for kava is needed in order to verify the organic production methods used for the growth of the industry, validate these methods, and grow in that niche market.

-

-

Kava Production in Hawaii vs other Pacific Islands

Hawaii has a long history of growing and consuming kava and it has experienced a surge in the past two decades. In 1998, the Association for Hawaiian Awa (the Hawaiian name for Kava) was formed as a “non-profit organization for research, education, and preservation of the cultural and medical awa (kava) plant.”

Hawaiian kava farmers have been using modern techniques and technologies that vary greatly from the rest of the Pacific Islands and are “a much different approach to kava production.” The guide provides information on these Hawaiian methods for kava producers outside of Hawaii and in other Pacific Islands should they be interested in experimenting but recommend that they do so “on a small scale and with caution.”

The basic kava production systems in Hawaii vary depending on the type of land the kava is planted:

-

Deep soil

-

In Hawaii, these types of lands were formerly used for sugar and pineapple and are often depleted of nutrients. In order to suit kava production, they need to be “deep-ploughed and rotor tilled with compose and/or manure.” Other minerals may also be added if needed and then ridges are formed in order to promote proper drainage.

-

-

Rocky soil

-

For kava preparation, these types of lands are prepared similarly to deep soil lands but “with no deep ploughing because of the often shallow soils.”

-

-

Forested and rocky with limited soil

-

These lands usually contain trees so the kava is “grown among and under the trees on mounds of cinder, soil, compost, and fertilizer mix.”

-

-

Rocky with very little or no soil

-

In Hawaii, these types of land were often formerly used to grow papaya or anthurium until fertility depletion, ring spot virus, or anthurium blight. Preparation for kava production entails clearing the lands of weeds and then the kava is “grown in mounds of a mixture of cinder, soul, and compost with fertilizer added.”

-

Smaller kava producers sometimes use the “basket system” which consists of wire baskets lined with weed mats and filled with a mix of cinder, soil, compost, and fertilizer. This system saves time and money, saves on labor costs, and eases pest and disease control. The ease of harvesting thus makes this an “attractive alternative for small growers wanting to supplement their income.”

The guide then goes over fertility management, weed management, irrigation, spacing and shading, and pruning which do not differ significantly from the overview given previously in the guide.

Expanding Hawaiian Kava Production

The guide then details a fast propagation method specific to Hawaii where “a major constraint to expanding kava production is a lack of planting materials.” This has resulted innovative farming methods in order to optimize the amount of planting materials obtained from kava plants. One of these innovations is the “tipping and pinching approach” where the “buds are stimulated to grow into shots while they are still on the plant rather than after planting, with the result that you can have much faster growing plants once they are put in the ground.”

A more detailed outline of this innovative method is summarized below (taken directly from the guide):

-

Plant preparation (before taking cuttings)

-

Fertilize plants 1-2 weeks before tipping

-

Tipping: the removal of the primary branch tip

-

Tip only hard, woody branches

-

Use only nodes from primary branches

-

-

Pinching: the removal of the upper portion of the axillary bud, leaving the base of the node. The purpose of pinching is to prevent damage to the sprouted bud (breaking of the node). In addition, the pinching stimulates 3-4 eyes to come out of the base of axillary bud giving 3-4 stems from one plant rather than the usual 1 stem.

-

Pinching should be done when axillary shoots are at least 2.5cm; the larger the shoots, the better.

-

-

Removing nodes from the stem

-

Cutting individual nodes

-

Cut with a sharp and clean device

-

Cut close to the node

-

Place cutting into a plastic bucket; damp sphagnum moss is helpful to keep the cutting moist. Ensure the bucket is not in the sun or subject to heat.

-

Immediately transport to nursery.

-

This process can continue with multiple nodes but always leave one node at the bottom of the stem in order to prevent potential entry of fungi that can cause rotting of the rootstock.

-

-

Preparing Nodes in the Nursery

-

Lay nodes in trays with pinched axillary buds facing up

-

Dip the tray of nodes in fungicide and bactericide to prevent rot (optional); after soaking, rinse with fresh clean water and allow water to drain off until dry

-

Soak tray of nodes in seaweed extract and high phosphate foliar mix (optional)

-

Paint freshly cut node ends with pruning paint (optional)

-

Place tray on a bench in a mist chamber so the nodes are kept moist

-

-

Potting rooted notes

-

Use a 4 liter pot or bag so you can keep the plant in the same container until transplanting

-

Use sterile media where possible

-

preferred mix: 80% cinder/perlite, 20% compost

-

-

Drop or mist irrigation is recommended though watering daily is acceptable once the plants are well established

-

-

Start with 60-80% shade in the nurdery and gradually increase exposure to 60-70% and then 30% before transplanting

-

Fertilizer application can be done in several ways

-

Slow release

-

Foliar spray/soak

-

Manure tea or in the potting mix

-

High phosphate seaweed extract

-

-

The size of the plant at transplanting depends on field conditions

-

Small plants for shaded, weed-free, and/or pest-free conditions

-

Large for unshaded, weedy, and/or pest-ridden conditions

-

-

-

Organic Kava Production

At the time of publication of the guide, experiments with producing organic kava were underway including the efforts of Jim Henderson of Pu‘u O Hoku Ranch in Kaunakakai, Hawaii. In terms of fertilization, not much is known about what kava needs for high kavalactone content and vigorous growth—fertilization was thus often “based upon what is known of other plants’ needs.” However, kava does appear to be a heavy feeder necessitating foliar fertilization in order to keep the nitrogen at a high level for maximum growth. Steps for the production of organic kava according to Jim Henderson’s experiments are detailed below (taken directly from the guide):

-

Soil Evaluation

-

Nutrient levels in soil can vary greatly and thus a soil test is important in order to determine what to add to the soil and develop an appropriate soil fertility management plan.

-

-

Pre-plant application of one tonne/hectare of calcium (oyster shell lime) and one tonne/hectare of phosphorous (soft rock phosphate)

-

When possible, the field is planted with either Sudan grass or crotalaria (a legume that fixes nitrogen); both are known to kill nematodes. There are also other good tropical cover crops that can be used all of which crowd out the weeds and enrich the soil. Afterward, they are cut and plowed into the soil.

-

Three-month-old kava seedlings are planted 1.6 m apart on raised beds (30 cmx1.8m) made with a tractor and ridging attachment. Norwegian kelp (algit), fish or blood meal, and diatomaceous earth is planted at the same time. Compost is added at a rate of 28 kg per bed of 65m. A mulch over of chipped trees is overlaid on beds to a depth of 10cm.

-

There are windbreaks every 150m and rows of pigeon pea, gliricidia, and sesbania at closer intervals. Shading is not considered necessary.

-

There is not much pruning of the kava apart from propagation and culling out poor stems.

-

A foliar fertilizer spraying schedule begins after planting, ideally done every three weeks. The process can be improved upon with the use of spreader stickers (yucca extract) and oxygen and pH modifiers (hydrogen peroxide or vinegar).

-

When the kava is 6 months old, the kava is side dressed with phosphorous, lime, and blood meal. After 1 year, it is side dressed with algit and fishmeal (potassium and nitrogen).

False Kava: A Threat to the Kava Industry

One threat to the South Pacific kava industry that the guide highlights is “false kava.” False kava refer to other species within the Piper genus that do not contain kavalactones. The guide states that these species can be “sold to unsuspecting buyers here in the Pacific or shipped directly to overseas buyers, usually mixed in with true kava.” Once the kavalactone content is tested however, these shipments are usually rejected. False kava can then give kava producers and exporters a bad reputation in the international kava market. Species of false kava can include the following:

-

Piper aduncum

-

This species presents itself as a tree with flowers and leaves that are bigger and lighter green than kava. It was introduced in the 1920s and is now a “widespread weed in the wet and intermediate zones of Viti Levu, Fiji Islands.”

-

-

Piper auritum

-

This species causes the most confusion in Hawaii, but appears distinct from kava in its vein pattern and smell. It contains a central vein with smaller veins branching off of it while kava has 9-13 veins all spreading from the base of the leaf. And when crushed, the leaves smell strongly off safrole. When found in the leaves and stems, safrole is considered a carcinogen by the FDA.

-

-

Piper

-

Other members of the Piper genus—such as Piper wichmannii in Vanuatu—may be confused with kava. They are widespread throughout the Pacific Islands and do not contain kavalactones. Experienced kava produces will be able to detect the differences upon close examination of the plant’s leaves, stem, flowers, and plant form. When tried, these species will not have the same characteristics small of kava and can occasionally differ in color. The roots are also woodier and contain less starch, are not slender, and are not flexible.

-

The guide urges kava producers and consumers to understand these other species within the Piper genus reiterating, “Do not let the false kava destroy the reputation of kava from the Pacific.”

References

- Secretariat of the Pacific Community’s “Pacific Kava: A Producer’s Guide” (2001)

2 comments

Wow, never knew anything about this plant, website introduction is very informative. Peace and Love

Wow, never knew anything about this plant, website introduction is very informative. Peace and Love